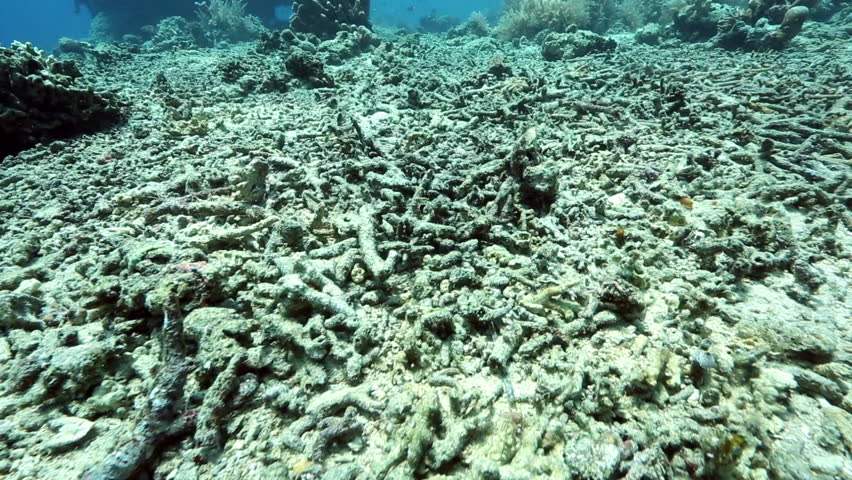

Climate Change Has Already Done in Half the World’s Coral Reefs

The oceans have long been the biggest buffer for humankind’s dangerous greenhouse-gas emissions. Around a quarter of all the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere since the 1980s—from driving cars, running factories and churning out electricity with fossil fuels—has ended up sunk into the waters.

As the planet has warmed from mounting emissions, the oceans warmed first and fastest, absorbing 90% of that excess heat.

A report released last month by the UN-based Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the foremost scientific authority on the subject, warned that damage to the oceans is accelerating and may be at the point of irreversibility.

That makes delicate coral reefs around the world something of a leading indicator for the collapse of the ocean ecosystem. Half of all reef systems have already been destroyed, putting a quarter of marine life at risk.

Even if global warming is limited to the 1.5-degree Celsius target outlined in the 2016 Paris Agreement—a longshot goal, at the current rate of emissions—the IPCC now concludes that “almost all warm-water coral reefs are projected to suffer significant losses of area and local extinctions.”

In a perverse consequence, lost reefs will leave nearby coastlines even more vulnerable to erosion and storms, as well as from accelerating sea-level rise, which could go up by as much as two feet this century as a result of glacier melt.

Corals are so sensitive to rising sea temperatures that you can see their demise. When water is too warm, corals enter a stress response and lose the symbiotic algae that give them their distinctive colors—a process known as bleaching. If a coral is severely bleached, chances of disease and death increase.

In 2014, an El Niño-driven coral bleaching event swept the world’s reefs that lasted three years—the longest and most damaging of its kind on record. Bleaching was evident in 75% of tropical reefs and brought nearly 30% to mortality level.

Reefs in the northern part of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef that had never bleached before lost nearly 30% of their shallow water corals in 2016. Reefs farther south lost another 22% in 2017. Only 7% of the reef avoided coral bleaching. In Japan’s Sekiseishoko Reef, East Asia’s largest, over 90% bleaching was observed, with 70% lost.

Many reefs—including those in Guam, American Samoa and Hawaii—experienced their worst bleaching ever documented. In the Northern Line Islands in the South Pacific, between 80 and 98% of total coral cover was killed.

High temperatures in 2015 impacted coral reefs throughout the western Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, with the western Caribbean hit hardest. In 2015 moderate to severe coral bleaching and disease impacted Florida’s coral reefs for the second year in a row.

In early 2016, bleaching in the Seychelles reduced the reef’s hard-coral cover by about half.

Some of the planet’s most important habitats are within 12 nautical miles from shore—the coral reefs, seagrass and mangrove areas plied by over 50 million fishers for food and livelihood. Reefs that manage to survive the onslaught of warming and acidification will be left with less marine diversity, the IPCC warns, which will “greatly compromise” seafood supplies and tourism revenue.

That could leave 680 million people who live in low-lying coastal zones in a bind, especially those in smaller island states. Fishing and tourism contribute an estimated $16 billion annually to 52 economies particularly intertwined with coastal reefs. Almost 20% of gross domestic product in the Maldives is directly tied to reefs.

Source: Bloomberg