The Unusual Job of the Cigar Factory Reader

Now that Havana is making preps to celebrate its 500th anniversary, this seems to be the perfect time to delve into one of the most unusual jobs ever seen, one that probably only exists on this island nation and nowhere else under the sun, a job that was born in Cuba’s capital: the cigar factory reader.

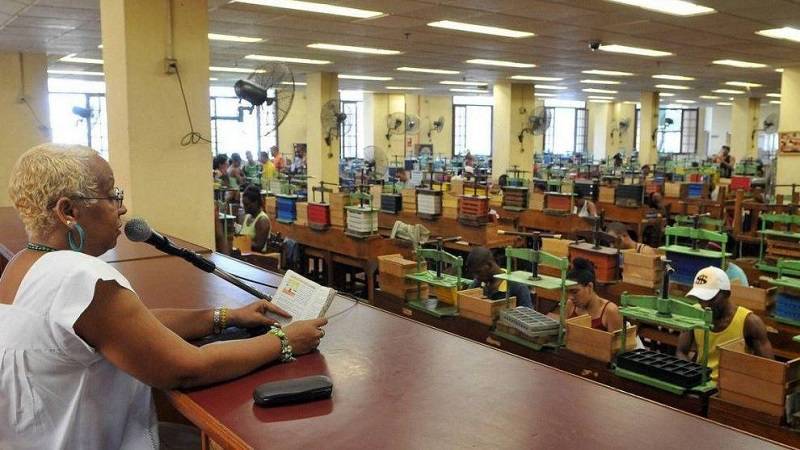

Put plainly, this is just a worker from the tobacco industry, usually a former cigar roller, whose job consists of reading texts out loud to entertain his coworkers in the vast workshops, let alone keep them posted on the latest developments around the world. What they read sways from daily newspapers and weekly magazines to great novels authored by famous writers from universal literature.

In the course of many decades, some books have had tremendous acclaim among tobacco industry workers. Two good cases in point are Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare and The Count of Montecristo by French author Alexander Dumas. The influence these books exerted on the cigar rollers was so big that two of Cuba’s best-known cigar brands –Montecristo and Romeo y Julieta- were named after the two great volumes.

This character –he can’t be unlinked to the everyday going of Cuba’s cigar factories– emerged as a need back in the 19th century, a request made by cigar rollers to get some amusement during the course of their shifts.

The Origins

After Spain fostered the growth and harvest of tobacco in Cuba –it had turned out to be a big business in the 18th century– the number of planters and factories for the exportation of cigars accrued dramatically. Tabaqueria y el Lector Since the early 19th century, cigar factories started to have fame and prestige. By the mid-1800s, many of those factories began to churn out brands of their own as the tobacco harvest and the manufacturing industry picked up steam.

Cuba’s working class was born in the cigar factories. They used to spend long hours sitting behind their desks, blandishing their jackknives, rolling the leaves, making the vitolas and giving a refined finishing touch to each and every cigar. Under those circumstances, the idea of breaking that silence with the voice of a reader was whipped into shape.

The Evolution in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Some sources say it was back in 1864, at the Viñas de Bejucal workshop, where the figure of the cigar factory reader first came up, a peculiar character who has prevailed to date and has panned out to be one of Cuban culture’s most beautiful traditions. The experience arrived in the nation’s capital the following year and word has it the El Figaro Factory, owned by Julian Rivas, was one of the first locales that embraced the experience.

Quite soon, the practice of cigar factory readers caught on in some industries of Havana, not always with the owners’ approval, who now and then banned the readings because they thought their workers could get distracted, thus leading to productivity slowdowns. It’s said that Jacinto de Salas y Quiroga stood up heatedly for the reading of newspapers and books to amuse the cigar rollers.

Amid this controversy, intellectual Nicolas Azcarate got a word in edgeways for cigar factory readers from his tribune at the Guanabacoa Lyceum. The El Siglo (The Century) newspaper also supported the readings, joining hands with some owners of celebrated brands, such as Jose Cornelio Suarez and Jaime Partagas, whereas others snuffed it out because they were convinced the practice was only good for encouraging laziness.

The battle for the approval of cigar factory readers was won by the workers, who eventually proved the validity of a cultural project that, far from hampering productivity, could actually encourage outputs, let alone help the workforce acquire culture. The final decision was made at the 1892 Workers’ Congress, whose delegates applauded the initiative.

At the end of the day, the readers joined the factories’ payrolls and the practitioners acquired a number of different skills, not only for the impartial reading of the printed press, but also in the dramatization of novels.

The Trade Today

Today, this trade demands a reader with a good voice, accurate pitch, the ability to adjust to the different characters and situations, and even a good dose of imagination as some have been bound to come up with an end for a novel because the book’s last pages had been accidentally plucked out.

Readers –both men and women, because femmes are now allowed to apply for that job too– are highly-coveted characters in Cuba’s cigar factories, places that cherish not only the traditions of the trade, but also of the readings. And the wisdom, beauty and emotions they convey appear to have been mysteriously passed on to that matchless product called Habano.